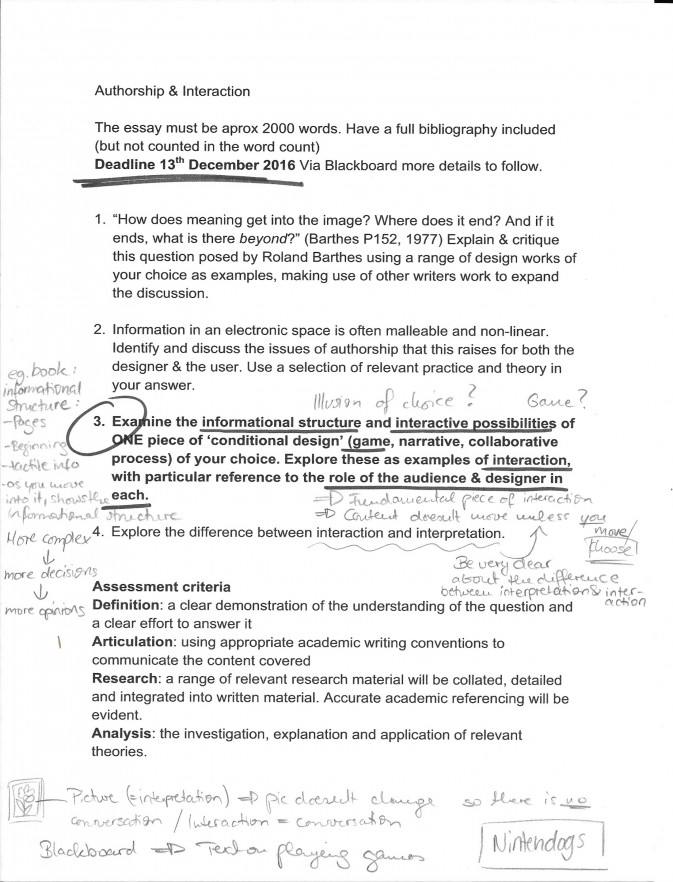

Examine the informational structure and interactive possibilities of one piece of ‘conditional design’ (game, narrative, collaborative process) of your choice. Explore these as examples of interaction, with particular reference to the role of the audience and designer in each.

Authorship and Interaction Design Stephanie Skarica – w1618332 13 December 2016

This essay will examine the informational structure and the interactive possibilities of the single and multiplayer pet simulation Nintendogs for the Nintendo DS (2005) considering the role of the audience as well as the designer.

This essay is structured by giving definitions about to what extent a simulation can be a game and analyse the playability of it. Following by explaining rules and functions of the Nintendogs and to what intensity the correlation between the designed outcome and the audience is. The essay will use the word player, user and participant for audience. The instruction booklet Nintendogs is explained as following: “Nintendogs is an interactive entertainment experience centered on puppies.” (Nintendo, 2005). Nintendogs was created 2005 in Japan by Hideki Konno and Shigeru Miyamoto and published by Nintendo Co. Ltd. (Dewinter, 2015).

The interface of Nintendogs consists of four elements, which are the device itself, the graphics, the audio system, the dual screen with the touch screen at bottom and the wi-fi connectivity. Nintendo DS is a handheld portable two-screen Gameboy device with one a touchscreen, action buttons, speakers and a microphone (Saunders and Novak, 2012). For the dog simulation game Nintendogs, it uses every single aspect of the Nintendo DS. The visual interface has a LCD display with 356x92pi resolution and therefore gives you a high range of colours which makes the graphics almost clearly to see. The Nintendo DS is also a “multimodal” device, because “[the] audio input systems translate an audio stream received via microphone to a game control [Nintendogs]” (Sigchi and Sigart, 2006). The player can use the touch-screen with the help of a stylus to operate with the system. This input method let the player have control over the simulation whereas seeing his result on the other non touch-screen. Nintendogs switches very often between those two screens depending on the player’s choice. If the audience wants to play with other dogs it can do so with the so-called “Bark-Mode”. This mode enables the player to meet other players via wifi connection.

Nintendogs is a simulation and therefore not a game according to (Costikyan, 1994). There are no end goals, victory and competition though the simulation contains contests; it is not the purpose of the game. But Prensky is of the opinion that simulations can become a game when adding learning and competing to it. For example in Nintendogs, without the three contests: Disc Competition, Agility Trial, and Obedience Trial the simulation would be “boring” (Prensky, 2001). Nintendogs has the goal in teaching the dog tricks and commands. Consequently you earn more money when training your dog and winning the competitions. Therefore you can buy new toys, food and even a beautiful new home for your dog. This kind of simulation is a game to some extent I would say.

When adding fun to the simulation, “different audiences have different ideas of what `fun ́ is.” (Prensky, 2001).

For this reason I would assume that even goals will be set variously. For one player the goal is to buy the most expansive house. To achieve this, he has to train his dog to compete best in the competition so that it gets money. Another player would set his aim to teach the dog every single trick Nintendogs provides. According to this, there is a game within Nintendogs, to certain extent.

The playability, which is in other words the informational structure, “refers to the overall user experience of a game, whereas usability more specifically refers to the user interface.”, according to

Saunders and Novak. User experience means what experience the user has and how the user is using it, in short, (relating to Nintendogs) - how the simulation is played by the player. User experience should focus on user ́s enjoyment especially in designing video games, as they are very pleasurable and playful (Korhonen, Montola, and Arrasvuori, 2009). The players are actively involved in the simulation and therefore competent and selective recipients of information (Egenfeldt-Nielson et al., 2015). Playability can also be gameplay in other words, it refers to the game dynamics, “how it feels to play a game”. Audio and visual aspects also influence this feeling (Egenfeldt-Nielson et al., 2015). Nintendogs has several different but very calming and relaxing sounds which supports the player`s feelings. The audience empathises and immediately establishes enjoyment through the game.

Nintendo EAD initiates with a virtual kennel where you can buy one of three virtual puppies of any breed that the simulation offers. There are three versions Nintendogs sold, each with a selection of six various breeds. After you chose (a) dog(s) you bring it to your virtual home where the tutorial starts. The player has to follow it, to get interactive with the dog. Nintendo EAD developed several steps to teach the player how to use the interface for interacting with the pet. First, the player has to touch the “paw print” on the touchscreen so that the player gets the attention from the dog (Nintendo, 2016). Secondly, the player has to give him a name to which he should listen. With the Nintendo DS built- in microphone the dog ́s name should be repeated several times until it can be typed in. It could be that the dog is forgetting its name, where the player has to redo the process again. The next instruction is only about practising calling the dog ́s name. The pronunciation should be clear. The player interacts with the dog over the voice recognition program (microphone) and with the stylus on the touchscreen. Now after the dog has successfully remembered its name the player has to teach him the “sit” command. With the stylus sliding down the dog ́s head makes the dog sit. For this, the player has to follow instructions again. When you got the dog to sit, a yellow light bulb symbol appears on the touch screen. The player can touch this item with the stylus and reward the dog. The command should be repeated several times until the player can type it in. In Nintendogs later on, the light bulb always appears when the dog does the command. The sound also changes and I would maintain it has only an effect on the player as it doesn ́t affect dog ́s behaviour. Before the player can start the actual game both the virtual dog and the audience have to complete all instruction steps.

Now you have access to various functions the simulation offers: e.g. the supplies list, where you can choose your type of supply, e.g. toys or food. Nintendogs also allows the player by touching the “Go Out” Button to go to a number of places with the dog. It can either go shopping with you, go for a walk, attend to contests or play with another Nintendogs owner via bark mode. This wireless mode on Nintendo DS device enables players to interact with real people. It allows both pet owners to play with their pets together. It doesn’t affect the pet directly but the player. Before you start communicating with another puppy you decide whether or not to bring a present with you for the other owner. When the player receives a present it will automatically be saved in the suppliers list. Now you can choose whether you use this present for your dog or sale it, so it gives you money. Generally, there are times when the dog gets presents suddenly while e.g. going for a walk. This game system is also called “random reward schedules” (Cook, 2005). Cook describes, “[B]y having intermittent reinforcement, the designer maintains the enjoyable addictive nature of the reward for a longer period of time.” This means, that the designer developed Nintendogs in that way, achieving the player ́s curiosity and therefore a kind of addiction. As Prensky says, “You want them to think that if they’re succeeding in the game (...)”.

All the functions are accessible for the player, but there are still rules the designer created. There is a so-called “Time penalty” (Cook, 2005), that when the player hasn ́t played for a long time, the dog gets angry, thirsty, hungry and generally in a bad mood. It could be that he also doesn ́t remember his commands and tricks the user taught him. Because of this penalty, I argue that Nintendogs has an iterative quality of interactivity. Iterative means a process that cycles back and forth (Salen, Zimmerman, and Tekinba, 2003). The penalty example shows that the simulation can be played non- repetitive, if the player is playing all the time. But even that is impossible because the designer generated a 30-minute timer in certain functions, like e.g. contests or walk (Cook, 2005). This consequently means, that the player is forced to play the game often so that it achieves its individually set goal, e.g. be the best in one contest. But when playing, the user has to consider the time restrictions.

Due to this, I maintain that the player doesn ́t actually have a choice. It has to some extent, while playing in the so-called “sandbox level”. The virtual home location acts as a “(...) sandbox area for introducing new actions (like the Frisbee)”, (Cook, 2005). On one hand you can play with your dog until it gets exhausted but on the other hand, you cannot feed the dog how much you want. For this, the designer always paid the attention to make the game as realistic as possible, so that the user is learning some kind of way to take care of a dog. But the player has the freedom to choose the type of toy he wants to interact with. The user even has the choice to fail in a contest or to not get a present while walking on the virtual street. The participant has control over the outcome in some ways so that he thinks that he has a choice. Zimmermann (2003) says “[w]hen a player makes a choice within a game, the action that results from the choice has an outcome.” According to this statement, it is also a matter of interactivity, how the player uses the virtual character in the simulation to do things (Zimmermann, 2003). Nevertheless, “[a]ll choices in video games, are predetermined by game designers.” (Zimmermann, 2003). Nintendogs is an example of interactive narrative, where participants create a story through their actions (Riedl and Bulitko, no date). This means, that the simulation has a story and it depends on what the player brings to it. In the virtual world of Nintendogs, the designer let the user believe that he is the “co-creator” of the story and that decided actions alter the outcome of the story (Riedl and Bulitko). But those actions are not limitless, as the user has to follow certain rules. Those regulations have a structure, which are in Nintendogs, fixed buttons. Those given options are created to be a part of the simulation design (Berger, 2002). Everything explained above also underlines with Greg Costikyan ́s statement about interaction: “Now we’re not talking about “interaction.” Now we’re talking about decision making – interaction with a purpose.” (Costikyan, 1994). Boellstorff also agrees with the argument that the player is a creator: “By exercising “the idea of the self as a creator,” children contribute to the creation of their own worlds. (Boellstorff, 2008). Nevertheless, the role of the designer and as well as the player come together to create a dataset by adding information and meaning to it (Meadows, 2003). Malaby adds that the designer “carefully craftes the logic of the game” (Malaby, 2007). Consequently it can be said that the designer and the player both create the outcome.

To bring it all together, I totally support the opinion from Kohler: “Nintendogs' intuitive interface and relaxing, open-ended gameplay [...] attract a wide audience outside the usual gamer demographic.” (Kohler, 2016). This is true, when looking at the statistics with the top selling Nintendo DS titles worldwide. As of March 31, 2016 Nintendogs was the second top selling Nintendo DS game with 23.96 million units sold (Statista, 2016).

Bibliography

Berger, A. (2002) Video games: A popular culture phenomenon. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Boellstorff, T. (2008) Coming of age in Second life: An anthropologist explores the virtually human. United States: Princeton University Press.

Cook, D. (2005) Nintendogs: The case of the non-game that barked like a game. Available at: http://www.lostgarden.com/2005/06/nintendogs-case-of-non-game-that.html (Accessed: 9 December 2016).

Costikyan, G. (1994) I Have No Words and I Must Design. Interactive Fantasy. Available at: http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/05164.51146.pdf (Accessed: 10 December 2016).

Dewinter, J. (2015) Shigeru Miyamoto: Super Mario Bros., donkey Kong, the legend of Zelda. United States: Bloomsbury Academic USA.

Egenfeldt-Nielson, S., Smith, J.H., Tosca, S.P. and Egenfeldt-Nielsen, S. (2015) Understanding video games: The essential introduction. 2nd edn. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Kohler, C. (2016) Barking mad for Nintendogs. Available at: http://archive.wired.com/gaming/gamingreviews/news/2005/08/68558 (Accessed: 10 December 2016).

Korhonen, H., Montola, M. and Arrasvuori, J. (2009) Understanding playful user experience through digital games. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.586.7146&rep=rep1&type=pdf (Accessed: 08 December 2016).

Malaby, T.M. (2007) ‘Beyond play: A new approach to games’, Games and Culture, 2(2), pp. 95–113. doi: 10.1177/1555412007299434.

Nintendo. (2005) Available at: https://www.nintendo.com/consumer/gameslist/manuals/DS_Nintendogs.pdf (Accessed: 9 December 2016).

Nintendo (2016) Getting started with the game. Available at: https://www.nintendo.co.uk/Support/Nintendo- DS-Lite/Games/Nintendogs/Getting-started-with-the-game/Getting-started-with-the-game-618875.html (Accessed: 9 December 2016).

Prensky, M. (2001) Digital game-based learning. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Salen, K., Zimmerman, E. and Tekinba, K.S. (2003) Rules of play: Game design fundamentals. Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press.

Saunders, von K. and Novak, J. (2012) Game development essentials: Game interface design. Available at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=PbQKAAAAQBAJ&pg=PT383&dq=nintendogs+interface&hl=de&sa=X&re dir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=nintendogs%20interface&f=false (Accessed: 2 December 2016).

Sigchi and Sigart, S. (2006) Toward human robot collaboration: Proceedings of the 2006 ACM conference on human-robot interaction, march 2-4, 2006, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA ; HRI 2006. New York, NY: ACM Press.

Staley, D.J. (2013) Computers, visualization, and history: How new technology will transform our understanding of the past. 2nd edn. United States: M.E. Sharpe.

Statista (2016) Nintendo DS top selling titles worldwide 2016 | statistic. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/248205/top-selling-nintendo-ds-titles-worldwide/ (Accessed: 10 December 2016).

Riedl, M.O. and Bulitko, V. (no date) Interactive Narrative: An Intelligent Systems Approach. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.309.2074&rep=rep1&type=pdf (Accessed: 9 December 2016).

HOME

HOME